Scientific Illustration Part 1a: Kunimasu

While I was working at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, in my free time I had been experimenting with scientific-style illustration of fishes. In particular, I had drawn a bluespotted sunfish and a satinfin shiner on Procreate, a digital drawing app I use with my iPad.

Just for kicks, I decided to post them in some of the online fish enthusiast communities I am a part of, and one of my fish-related acquaintances noticed it. This particular acquaintance of mine is a graduate student working on his dissertation. We discussed matters for a little while, but soon enough I found myself commissioned for a project that would involve the digital illustration of 6 salmonids for a research manuscript.

The first project was an illustration of a kunimasu, or black kokanee. This landlocked sockeye salmon variant, considered a separate species (Oncorhynchus kawamurae) by some, is endemic to Lake Saiko in Japan, orginally endemic to Lake Tawaza but now extinct from that waterbody. The species was thought to be extinct in 1940, but was found to be alive in 2010 in Saiko, where there was an introduction many years ago that was thought to be unsuccessful. Interestingly enough, this species spawns considerably deeper than other kokanee or sockeye salmon, at depths of up to 300 m!

While the fish was certainly fascinating, it presented some difficulty in trying to illustrate it. I did not have access to any specimens, and references online were spotty, but I managed to find some sources through primary literature.

This chart was particularly helpful; was able to find use scale counts, fin ray counts, proportion measurements, etc to make sure my illustration was scientifically accurate.

I started with an outline to get the proportions of the fish set before moving in to the painting stage.

Then I got to work on the head. I like to start with it especially on salmonids in favor of attacking the body as a whole, because the flank scales present a different surface than the head, which is devoid of scales and thus has a different texture.

Then, using a green filler for the flank, I started working on the fins. In later illustrations I would get the flank first, this seemed to be advantageous with regards to connecting the fins to the body.

A glimpse into the different layers building up the fish

Not a bad setting to be drawing!

Taking care of minute details and making sure everything is scientifically accurate, including things like fin ray branching

I then began work on flank coloration, this was simple as I mostly smudged color in as filler.

Then came the difficult part: scaling. I ended up creating a custom brush on Procreate with which I could dot the scales onto the body, but it still took considerable time, especially considering that I needed to get scale counts as accurate as possible. This was my first attempt at such a technique, so the results were less than optimal, but in later illustrations I got better at it.

Body fully scaled, with spot patterns illustrated.

Adjusting coloration.

To ensure accuracy, I sent out copies of my draft illustration upon completion to experts on O. kawamurae, including the scientist who rediscovered them in 2010. With their feedback, I made necessary adjustments.

This is the final version.

More to come!

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scientific Illustration Part 1b: Stream-spawning sockeye salmon

The next commission in the series of salmonids was a male spawning sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka) of a stream-spawning variety.

The significance of the stream-spawning aspect of this fish was that stream spawning sockeye males develop a significantly less pronounced "hump" when spawning due to selective pressure from bear predation as opposed to the salmon that spawn in lakes. The thinner build makes it harder for bears to latch onto, and salmon that spawn in lakes are usually more out of the reach of bears than the stream-spawning ones.

This one, in terms of finding references, was significantly easier than the kunimasu. See examples below:

As usual, I began with the outlined proportions.

Then proceeded to work on the head.

With this fish, I paid particular attention to the various patterns, scratches, and coloration present on that characteristic green sockeye head.

With this one, I opted to start with the flank as opposed to the fins, as I felt this was a better method.

When scaling, I start with creating the set of scales along the lateral line—to make sure I have the correct number and the spacing/size. On this fish my scaling was significantly more detailed and neat.

One salmon has a lot of scales. I also decided with this fish to do the scales prior to more detailed body work in order to avoid needing to change coloration to fit the dullness of the scales, which were created using white at a low opacity.

Looking better....

The caudal fin is underway.

Here you can see the processes involved with drawing the caudal fin: first comes ray definition, then the gradual addition of layers to build up the final image.

And the final version:

One more sockeye to go!

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scientific Illustration Part 1c: Lake-spawning sockeye salmon

The next illustration after the stream-spawning sockeye was the lake-spawning variant. The big morphological difference between the two is the body shape; see comparatively thick males below.

With that being said, the illustration of this fish was significantly easier in that I could retain the head and fins of the previous illustration, do a certain degree. This is one of my favorite advantages to using digital media for projects like these. With traditional mediums, such replication would be impossible.

That made the primary objective creating a new sockeye body.

Which, of course, required an entirely new set of scales, a tedious process (if that hasn't been made clear already). But I had noticed my scaling was growing more and more efficient.

The scaling opacity is changed, and then I work on coloration detail to generate the final product.

Boom.

This is the last salmon illustration commission. The next three are salmonids as well, but of a different genus from a different continent!

___________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scientific Illustration Part 1d: Ferox Trout

After finishing the sockeye salmon, I was off to Europe.

Not literally, but in the sense that I was drawing European salmonids, in this case three varieties of brown trout (Salmo trutta) that diverged in a single waterbody: Lough Melvin, Ireland.

The first such variety was the ferox trout, a brown trout variant that I eager to draw, simply because of the size, beauty, and power of these lake-run brown trout that consume a diet of mostly fish and grow to extreme size.

Historically, ferox trout have been described as S. ferox, a distinct species and reproductive isolated from S. trutta, but current literature suggests that they are not in fact a distinct species because separate populations in various lakes may have arisen independently in their respective waterbodies.

Regardless of taxonomy, however, I was absolutely floored to have the opportunity to draw this fish, and so I got to work on it immediately after finished the salmon.

As per usual, I began with an outline of the fish to make sure proportions were in order.

Then head work commenced. With this fish in particular I payed much attention to detail, probably because I was so invested in making sure the final product was as good as it could be.

The file sizes on these documents are huge; I think this one was 6000 x 8000 pixels. The large size allows me to work with a very high level of sharpness and detail.

As head worked continued, I found a challenge in illustrating the metallic nature of parts of the opercle, but I believe the final effect I decided on was the right decision with the addition of some light blues to complement the grays and whites and to give it a silver effect.

I started the flank by setting a base color gradient before scaling.

Then came the arduous process of laying out each scale, one by one.

In the meantime, I adjusted the body coloration some. Another advantage of digital media: I was able to manipulate color settings of layers and groups very easily and quickly, something unattainable with traditional mediums.

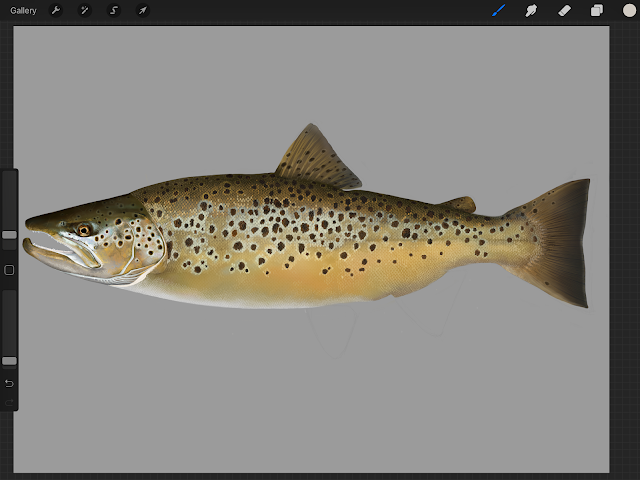

Once the fish was fully scales, I began work on the trout's spotting. I chose a rather densely spotted specimen, and added blue-grey highlights for the halos around the spots.

If I thought the scaling was hard, this part was a whole other level. With the salmon, I had managed to get away with not adding detail to each individual scale because the scales weren't defined enough to warrant that kind of attention. With the brown trout, however, the scales were defined quite markedly and thus each scale needed attention.

Below you can see the beginning of scale details.

A mid-scale detailing shot, before adding layers of color in various places between and on top of existing layers.

Here the scale detail is nearing completion. For this particular ferox I chose a buttery-yellow coloration, but the actual coloration of ferox can vary greatly, from nearly orange to silver to very dark brown.

Once scale work was complete, then came the fins, which at this point seemed like a piece of cake after drawing out every scale.

The caudal fin—note the scale work around the fin rays.

How fins are generally layered:

And the final version... or was it?

Upon further talk with professors, the student, and experts it became apparent that the particular ferox of Lough Melvin were generally more silver in coloration than yellow.

However, digital media made this adjustment as easy as changing some values on a slider, and brushing up some other minor changes like the addition of darker pigment on the belly.

There you have it; the ferox trout. From the salmon to this fish, I felt like I had made a leap in skill; from a technical standpoint the brown trout illustrations are, in my opinion, far superior. Two more brown trout are to follow.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scientific Illustration Part 1e: Gillaroo

Since it is a benthic feeder, it has a subtle overbite. This attribute I admittedly struggled with, playing with different versions of head structure until I created one that I felt was adequate.

Once I had finally gotten the head structure down, painting began. This fish was especially fun to draw because of all the bright yellows I was able to use, as opposed to the usual muted colors with most species.

As with the ferox, while illustrating the gillaroo I paid attention to maintaining a high level of detail and structural accuracy, another reason why I usually start with the head. When I begin an illustration is when I have the most motivation, a statement that probably rings true for most artists. And since the head can arguably be the most significant part of a scientific illustration, considering that it is usually the point of entry for an onlooker, it is important that it receives the most attention and quality of workmanship.

Scaling. With these later illustrations I took less screenshots of in-progress work, as I had gotten used to the rhythm of producing these fish.

After the scaling, I transitioned to patterning. The gillaroo also have prominent and plentiful red spots, another morphological difference separating it from ferox trout.

Scale detailing (ugh). But the final product is always worth the effort!

As I finished the body, the reddish fins of the gillaroo began to materialize.

And there's the gillaroo.

For some reason I didn't enjoy this as much as I did the ferox; it's probably because I feel that the ferox is generally a more aesthetically pleasing fish. But the next brown trout I found quite attractive, even more so than the ferox.

Not literally, but in the sense that I was drawing European salmonids, in this case three varieties of brown trout (Salmo trutta) that diverged in a single waterbody: Lough Melvin, Ireland.

The first such variety was the ferox trout, a brown trout variant that I eager to draw, simply because of the size, beauty, and power of these lake-run brown trout that consume a diet of mostly fish and grow to extreme size.

Historically, ferox trout have been described as S. ferox, a distinct species and reproductive isolated from S. trutta, but current literature suggests that they are not in fact a distinct species because separate populations in various lakes may have arisen independently in their respective waterbodies.

Regardless of taxonomy, however, I was absolutely floored to have the opportunity to draw this fish, and so I got to work on it immediately after finished the salmon.

As per usual, I began with an outline of the fish to make sure proportions were in order.

Then head work commenced. With this fish in particular I payed much attention to detail, probably because I was so invested in making sure the final product was as good as it could be.

The file sizes on these documents are huge; I think this one was 6000 x 8000 pixels. The large size allows me to work with a very high level of sharpness and detail.

As head worked continued, I found a challenge in illustrating the metallic nature of parts of the opercle, but I believe the final effect I decided on was the right decision with the addition of some light blues to complement the grays and whites and to give it a silver effect.

I started the flank by setting a base color gradient before scaling.

Then came the arduous process of laying out each scale, one by one.

In the meantime, I adjusted the body coloration some. Another advantage of digital media: I was able to manipulate color settings of layers and groups very easily and quickly, something unattainable with traditional mediums.

Once the fish was fully scales, I began work on the trout's spotting. I chose a rather densely spotted specimen, and added blue-grey highlights for the halos around the spots.

If I thought the scaling was hard, this part was a whole other level. With the salmon, I had managed to get away with not adding detail to each individual scale because the scales weren't defined enough to warrant that kind of attention. With the brown trout, however, the scales were defined quite markedly and thus each scale needed attention.

Below you can see the beginning of scale details.

A mid-scale detailing shot, before adding layers of color in various places between and on top of existing layers.

Here the scale detail is nearing completion. For this particular ferox I chose a buttery-yellow coloration, but the actual coloration of ferox can vary greatly, from nearly orange to silver to very dark brown.

Once scale work was complete, then came the fins, which at this point seemed like a piece of cake after drawing out every scale.

The caudal fin—note the scale work around the fin rays.

How fins are generally layered:

And the final version... or was it?

Upon further talk with professors, the student, and experts it became apparent that the particular ferox of Lough Melvin were generally more silver in coloration than yellow.

However, digital media made this adjustment as easy as changing some values on a slider, and brushing up some other minor changes like the addition of darker pigment on the belly.

There you have it; the ferox trout. From the salmon to this fish, I felt like I had made a leap in skill; from a technical standpoint the brown trout illustrations are, in my opinion, far superior. Two more brown trout are to follow.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scientific Illustration Part 1e: Gillaroo

Following the ferox was the gillaroo, this variety (considered S. stomachicus by some) is endemic to Lough Melvin, which the ferox trout is not. And unlike the ferox, this brown trout is relatively small and is usually bright yellow in coloration. Instead of fish, its primary forage food is snails, and it inhabits shallower waters.

Since it is a benthic feeder, it has a subtle overbite. This attribute I admittedly struggled with, playing with different versions of head structure until I created one that I felt was adequate.

Once I had finally gotten the head structure down, painting began. This fish was especially fun to draw because of all the bright yellows I was able to use, as opposed to the usual muted colors with most species.

As with the ferox, while illustrating the gillaroo I paid attention to maintaining a high level of detail and structural accuracy, another reason why I usually start with the head. When I begin an illustration is when I have the most motivation, a statement that probably rings true for most artists. And since the head can arguably be the most significant part of a scientific illustration, considering that it is usually the point of entry for an onlooker, it is important that it receives the most attention and quality of workmanship.

Scaling. With these later illustrations I took less screenshots of in-progress work, as I had gotten used to the rhythm of producing these fish.

After the scaling, I transitioned to patterning. The gillaroo also have prominent and plentiful red spots, another morphological difference separating it from ferox trout.

Scale detailing (ugh). But the final product is always worth the effort!

As I finished the body, the reddish fins of the gillaroo began to materialize.

And there's the gillaroo.

For some reason I didn't enjoy this as much as I did the ferox; it's probably because I feel that the ferox is generally a more aesthetically pleasing fish. But the next brown trout I found quite attractive, even more so than the ferox.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scientific Illustration Part 1f: Sonaghan

The last commissioned illustration for this project was the sonaghan. Like the gillaroo, sonaghan are endemic to Lough Melvin, but they are even smaller, more silver in coloration, and feed in the middle of the water column as opposed to being mostly benthic feeders. Sonaghan are generally considered Salmo nigripinnis.

In my humble opinion, sonaghan are the most handsome of the Melvin brown trout, with jet black fins,a sliver body, and a rusty yellow cheek. They have a more elongate face and body suited for open water.

Like the gillaroo's head structure, the sonaghan's long body also gave me fits. I've found over the years that placing a ruler image can help because you can literally measure out how the dimensions of one part of the fish (pectoral fin, for example) compares with another (like distance from eye to edge of gill plate).

Ah, scaling.

In terms of patterning, the sonaghan was relatively simpler, but the simplicity I took to be a positive attribute, with just a few, hard black spots and some faded reds near the caudal peduncle.

Scale detailing underway.

The sonaghan's fins, as aforementioned, are particularly dark. This made it easier to draw, since I didn't have to worry about layer opacity as much. If, for example, a fish has especially clear fins, then opacity would matter because it would look different depending on the background. That's why I felt a neutral, middle-tone grey for this project was the right choice.

Sometimes I like to make notes on necessary adjustments to remember, or comments for my employer when I send them to routine update on my progress.

And there's the sonaghan. This illustration, my last for this project, is probably my favorite, although it's a close race with the ferox.

I will say that there was noticeable improvement in my technical ability over the course of this project, which is a trend I hope to continue in the future with more practice.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Scientific Illustration Part 2: Senegalese Fishes

After the 6 salmonids, I wasn't sure if I was going to be doing any more scientific illustrations. But sure enough, another one popped up, and this one required work of a significantly simplified style, which was in hindsight very good, as school was just about to begin.

I was commissioned to draw simplified illustrations of 10 Senegalese fish species that have a potential to control the disease schistosomiasis by eating the host snails which carry the disease at one of its life stages.

Because these are simpler and took much less time, I don't really have any images of the in-process work.

However, these are going to be published in the American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene!

This is the research paper:

Arostegui MC, Wood CL, Jones IJ, Chamberlin A, Jouanard N, Faye DS, Kuris AM, Riveau G, De Leo GA, Sokolow SH. In press. Potential biological control of schistosomiasis by fishes in the lower Senegal River basin. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene.

Synodontis ocellifer

Synodontis schall

Synodontis nigrita

Clarias gariepinus

Malapterurus electricus

Chrysichthys nigrodigitatus

Labeo senegalensis

Hemichromus bimaculatus

Citharinus citharus

Protopterus annectens

No comments:

Post a Comment